Before: The Honourable Justice Masuhara

Reasons for Judgment

| Counsel for the Plaintiff: |

J.J. Camp, Q.C., |

|||

| Counsel for the Defendants Infineon Technologies, AG and Infineon Technologies North America Corp.: |

K.L. Kay, |

|||

| Counsel for the Defendants Hynix Semiconductor Inc., Hynix Semiconductor America Inc., Hynix Semiconductor Manufacturing America, Inc.: |

F.P. Morrison, |

|||

| Counsel for the Defendants Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd., Samsung Semiconductor, Inc., Samsung Electronics Canada Inc.: |

R.E. Kwinter |

|||

| Counsel for the Defendants Micron Technology, Inc. and Micron Semiconductor Products, Inc., doing business as Crucial Technologies: |

D.M. Low, Q.C. |

|||

| Counsel for the Defendants, Elpida Memory, Inc. and Elpida Memory (USA) Inc.: |

T.J. Mallett |

|||

|

Date and Place of Trial/Hearing: |

August 13-16, 2007 |

|

||

|

|

Vancouver, B.C. |

|||

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction and Background

a) The Representative Plaintiff

c) Guilty Pleas and Settlements in the United States

e) Dynamic Random Access Memory

a) Disclosure of a Cause of Action

d) Class Proceedings as the Preferable Procedure

e) The Suitability of the Proposed Representative Plaintiff

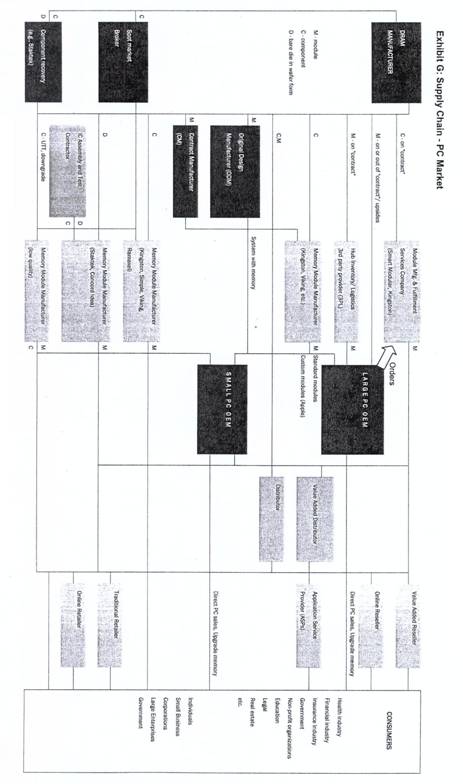

Appendix A: Supply Chain – PC Market

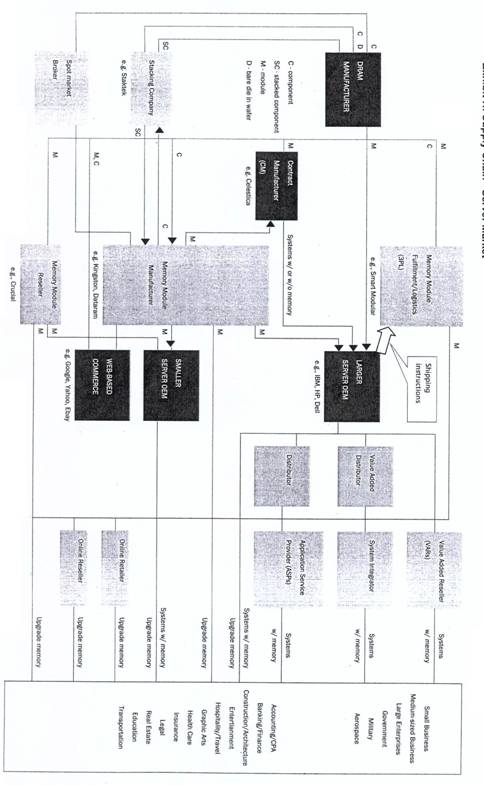

Appendix B: Supply Chain – Server Market

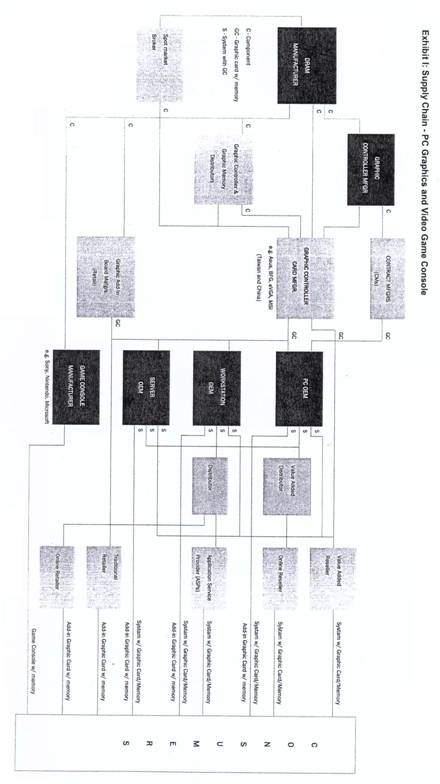

Appendix C: PC Graphics and video Game Console

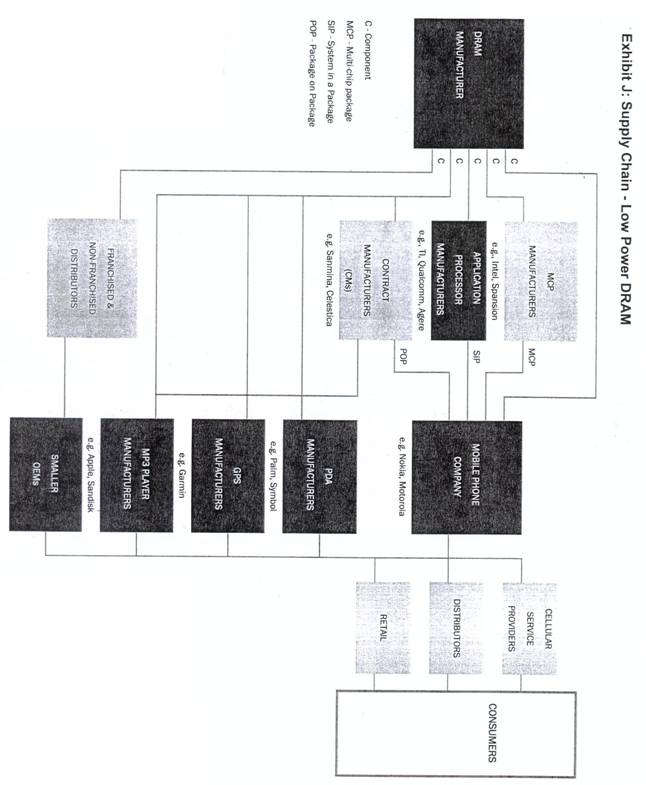

Appendix D: Supply Chain – Low Power DRAM

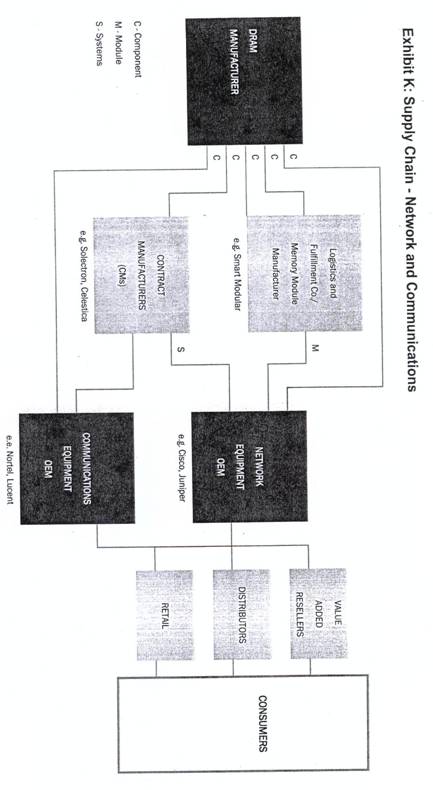

Appendix E: Supply Chain – Network and Communications

I. Introduction and Background

[1] This is an application for certification of a class action under the Class Proceedings Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 50 (the “Act”) by the plaintiff Pro-Sys Consultants Ltd. (“Pro-Sys”).

[2] The proposed action is founded on the basis that the defendants engaged in an international price fixing conspiracy with respect to the sale of computer memory chips, called dynamic random access memory (“DRAM”) from April 1, 1999 to June 30, 2002. DRAM is an essential component in virtually all electronic products used today, including: mainframes, servers, laptops, automobiles, global positioning devices, cellular phones, cameras and video games.

[3] The defendants (except for Micron) have been criminally convicted in the United States with respect to DRAM price-fixing and have collectively paid $731 million (USD) in fines. Some executives have also accepted plea bargains to pay fines and to serve varying periods of imprisonment.

[4] The plaintiff, on behalf of the proposed Class Members who are defined below, says that the defendants’ price fixing conspiracy violated the criminal law provisions of the Competition Act, R.S.C, 1985, c. C-34, and constitutes illegal and unlawful conduct which allowed the defendants to charge the Class Members more than they would have charged but for the illegal conduct (the “Overcharge”). Damages are sought in the amount of the Overcharge, or restitution of the defendants’ illegal profits.

[5] This is apparently the first application in Canada with respect to certifying a class action that includes both direct and indirect purchasers. Direct purchasers are those who purchased DRAM or products containing DRAM directly from the primary source of the product. In this case the defendants are the primary source. Indirect purchasers are those who purchased the subject products in transactions subsequent to the direct purchase. A key aspect of this application is the consideration of whether the Overcharge can be identified as having been “passed through” to the indirect purchasers on a class-wide basis. The ability to sustain a class action in relation to indirect purchasers in price fixing cases has been the subject of considerable commentary in the authorities in North American jurisprudence.

[6] The plaintiff’s specific claims against the defendants are as follows:

(a) contravention of Part VI of the Competition Act, giving rise to damages under s. 36 of the Competition Act;

(b) tortious conspiracy;

(c) tortious interference with economic interests;

(d) restitution claims of unjust enrichment, waiver of tort, and constructive trust; and

(e) punitive damages.

[7] The plaintiff defines the proposed class as follows:

The plaintiff and all persons resident in British Columbia excluding the defendants and their present and former parents, subsidiaries and affiliates, and the judge hearing this application and his or her immediate family, who purchased dynamic random access memory (“DRAM”) or products which contained DRAM in, into or from British Columbia between from April 1, 1999 to June 30, 2002 (the “Class Period”) (collectively, the “Class Members”).

[8] The plaintiff’s written submission clarifies this definition to include those who bought DRAM directly, as well as those who bought DRAM or products containing DRAM indirectly.

[9] The defendants concede that they have conspired to price fix with respect to DRAM in the United States, but they challenge the availability of civil remedies, the appropriateness of class certification generally, and that certification is being sought in Canada and more particularly in British Columbia.

a) The Representative Plaintiff

[10] Pro-Sys is a consulting business registered pursuant to the laws of British Columbia. In particular, it purchased a Toshiba Satellite 5000 laptop computer from London Drugs in Richmond, British Columbia on March 29, 2002 for $2,997.97 plus tax.

[11] The proposed Class Members are acknowledged to consist largely of indirect purchasers.

[12] Infineon Technologies North America Corp. (“ITNA”) is a subsidiary company of Infineon Technologies AG (“ITAG”). The former parent of this company was Siemens. ITNA carried on the business of ITAG in North America during the Class Period. Together, ITNA and ITAG are collectively referred to herein as “Infineon”.

[13] During the relevant period, the vast majority of Infineon DRAM sold into Canada came through Infineon’s San Jose office, and was in the form called SGRAM for use in graphics applications. It had no sales office in Canada, nor did it make any direct sales of DRAM in British Columbia during the Class Period. Infineon’s sales of DRAM into Canada as a whole represented less than 1% of its total sales of DRAM in North America during the Class Period. Infineon’s total DRAM sales billed to Canada during the Class Period was approximately $22 million (USD). Infineon has records of its direct sales but it does not have records of what happened to its product subsequent to that sale.

[14] Hynix Semiconductor Inc. (“HS”) is a Korean corporation. Its predecessors included Hyundai Electronics Co., Ltd. and LG Semiconductor Co., Ltd. Hynix Semiconductor America Inc. (“HSA”) is HSA’s North American, California based subsidiary. Hynix Semiconductor Manufacturing America, Inc. (“HSMA”) is an Oregon-based manufacturing entity. Together HS, HSA and HSMA are collectively referred to herein as “Hynix”.

[15] During the relevant period, Hynix produced DRAM in two forms: individual chips and modules. Hynix had one direct purchaser in British Columbia during the Class Period, Seanix.

[16] Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. (“SE”) is an international manufacturer of electronics. Samsung Semiconductor, Inc. (“SS”) is a subsidiary and affiliate of Samsung Electronics with respect to the semiconductor line of business in the United States. Samsung Electronics Canada, Inc. (“SEC”) and Samsung Electronics America, Inc. (“SEA”) are subsidiaries and affiliates of SE with respect to the multimedia and home appliances line of business. Together, SE, SS, SEC and SEA are collectively referred to herein as “Samsung”.

[17] Samsung’s product lines are divided broadly into three major categories: a) multimedia and home appliances, b) semiconductors (including DRAM units), and c) information and telecommunications.

[18] During the proposed Class Period no direct sales of DRAM were made by Samsung into British Columbia. There was and is no Samsung affiliate company with respect to the semiconductor line of business, including DRAM, in Canada. Neither SEC nor SEA has ever had any involvement in the manufacture, sale or distribution of semiconductors including DRAM.

[19] Samsung was released from all claims related to all direct sales of DRAM that occurred in the United States.

[20] Micron Technology, Inc. (“MT”), located in Boise, Idaho, is the parent company of Micron Semiconductor Products, Inc. (“MSP”), which sells DRAM directly through Crucial Technologies (“CT”). Together, MT, MSP and CT are collectively referred to herein as “Micron”.

[21] During the relevant period, Micron primarily sold DRAM products under three brand names: Micron, SpecTek, and Crucial. Under these brands, Micron produces DRAM in several forms including memory modules that can be inserted into a PC. During the Class Period, Micron’s direct DRAM sales into British Columbia totaled $2.3 million and were made primarily to one customer Seanix, who purchased about $1.8 million or about 80% of Micron’s British Columbia sales. The balance of British Columbia sales were made to about 2,500 Crucial customers.

[22] Elpida Memory, Inc. (“EM”) is a corporation headquartered in Japan. Elpida Memory (USA) Inc. (“EMUSA”) has its principal offices in Santa Clara, California. Together, EM and EMUSA are collectively referred to herein as “Elpida”. It is the smallest (in terms of global sales and global market share) of the defendant DRAM manufacturers. Elpida conducted business for no more than the last 18 months of the proposed 39 month Class Period. During the Class Period, it made no sales into British Columbia but made direct sales elsewhere in Canada.

[23] Of the five defendants, only Hynix and Micron made direct sales into British Columbia during the Class Period. The amount of these direct sales over the Class Period was $3.4 million (USD).

[24] During the Class Period, global revenues from the sale of DRAM were about $80 billion (USD), and the defendants collectively accounted for 76-82% of worldwide DRAM production.

c) Guilty Pleas and Settlements in the United States

[25] Beginning in June 2002, the United States Department of Justice (“DOJ”) initiated criminal investigations and proceedings with respect to DRAM price-fixing in the United States under anti-trust legislation.

[26] On or about December 17, 2003, following a subpoena from a Federal grand jury, an MT employee pleaded guilty to obstructing the grand jury’s investigation of a suspected conspiracy to fix the price of DRAM products sold in the United States.

[27] For being the first party to admit its misconduct, and for offering full cooperation with the investigation, Micron received amnesty from criminal sanctions for its involvement in price fixing in the DRAM industry.

[28] On November 11, 2004, Micron issued a press release admitting that DOJ had presented evidence that some of Micron’s employees and certain competitors in the DRAM market had engaged in price fixing.

[29] The conspiracy appears to have occurred during a period when DRAM prices decreased significantly and the defendants reached agreements to limit the rate of the price decline.

[30] Following this admission, some of the other defendants in these proceedings pleaded guilty and paid fines for participating in an international conspiracy to fix prices in the DRAM market. These parties and penalties are as follows:

· On or about September 15, 2004, Infineon agreed to plead guilty and pay a fine of $160 million (USD) and accrued interest.

· On or about April 21, 2005, DOJ announced that HS had agreed to plead guilty and to pay a fine of $185 million (USD) and accrued interest.

· On or about October 13, 2005, DOJ announced that SE and SS had agreed to plead guilty and to pay a fine of $300 million (USD) and accrued interest.

· On or about January 30, 2006, DOJ announced that EM had agreed to plead guilty and pay a fine of $84 million (USD) and accrued interest.

[31] In total, the defendants have collectively paid $731 million (USD) in fines.

[32] Criminal charges were also brought against individual employees of some of the defendants. These charges have led to the following criminal fines and prison sentences for participation in the international conspiracy to fix DRAM prices:

· On or about December 2, 2004, DOJ announced that four executives of Infineon had agreed to plead guilty, to pay $250,000 (USD) each in criminal fines, and to serve prison terms of four to six months.

· On or about March 1, 2006, DOJ announced that four executives from Hynix had agreed to plead guilty, to pay $250,000 (USD) each in criminal fines, and to serve prison terms of five to eight months.

· On or about March 22, 2006, DOJ announced that three executives from Samsung in the United States and Germany had agreed to plead guilty, to pay $250,000 (USD) each in criminal fines, and to serve prison terms of seven to eight months.

[33] The plea agreements entered into by the defendants with the U.S. authorities specifies only that original equipment manufacturers (“OEMs”) were “directly affected” by the conspiracy in the United States. The plea agreements are silent on the effects on indirect purchasers. The OEMs, all of which directly purchased DRAM from one or more of the defendants, were stated to be: Dell Inc., Hewlett-Packard Company, Compaq Computer Corporation, International Business Machines Corporation, Apple Computer Inc. and Gateway, Inc.

[34] Infineon, Samsung, and Hynix have settled direct purchaser class actions in the United States for a collective amount of approximately $160 million (USD).

[35] Actions continue with respect to indirect purchaser class actions.

[36] There is a difference in the laws between the United States and Canada in regard to anti-competitive offences. In the United States, antitrust laws require only evidence of a conspiracy in order to find that a wrong has been committed. In Canada, the laws require both a finding of a conspiracy and proof of harm.

[37] To date, the defendants have not paid any fines or penalties to Canadian regulators, have not paid compensation to Canadian consumers, and have not been charged with any criminal activity under Canadian law.

[38] The plaintiff presented the written evidence of three individuals.

[39] Dr. T. Ross, the UPS Foundation Professor of Regulation and Competition Policy in the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia. He provided economic evidence regarding the quantification of economic damages arising from anti-competitive practices, and in particular opined on the determination of an overcharge to direct and indirect purchasers of DRAM. He was cross examined by the defendants on his two affidavits.

[40] Mr. Leung, the president and director of Pro-Sys. He deposed that he purchased the aforementioned laptop and believes that it contains DRAM. He has no information as to the size of the class but is aware that a large number of personal computers containing DRAM have been purchased in British Columbia during and after the proposed Class Period.

[41] Mr. Mogerman, counsel for the plaintiff. He provided an overview of the application and similar proceedings in other jurisdictions, including in the United States. He covered the various plea agreements reached between the U.S. Department of Justice and the defendants and their employees. He also covered the qualifications of the firm representing the plaintiff and provided the litigation plan.

[42] The defendants presented the written evidence of five individuals.

[43] Margaret F. Sanderson, a vice-president and consultant in an economic consulting firm. She is the former Assistant Deputy Director of Investigation for the Canadian Competition Bureau. She provided economic evidence particularly with respect to harm and damage issues related to Class Members. She was cross examined by the plaintiff.

[44] Victor De Dios, a market research consultant who focuses on the semiconductor memory industry. He holds an M.B.A. from the Wharton School of Business. He has analyzed the DRAM industry for over 18 years. His evidence included a description of the DRAM product line and DRAM applications. The volume of production of DRAM during the Class Period, the average cost of DRAM as a share of the average price of different types of personal computers; a description of the supply chain and distribution of DRAM from manufacturers to consumers; a description of the timing of movement of DRAM from the supplier, through the OEM, distribution and value-added channels, and to the consumer of the electronic products containing DRAM; and an assessment of whether an average consumer can reasonably physically access DRAM in a product to inspect it.

[45] Jan Dierens, vice president of a successor company to the memory products division of Infineon. He has been in the semiconductor industry for close to 20 years. His evidence included the operations of Infineon, the different types of DRAM produced, the different performance characteristics of DRAM; the various methods in which DRAM was packaged, e.g. component and module form; the methods used by Infineon in selling its products and the arrangements it had for the same in Canada and elsewhere; and the information or lack thereof regarding resale of its DRAM.

[46] Jeong G. Nam, Director of Strategic Account Sales in the Sales and Marketing Division of Hynix. He has approximately 19 years of experience in the DRAM industry, mostly in marketing. He identified other DRAM manufacturers who are not named in this action, whose products were likely sold in British Columbia during the Class Period. He deposed that a consumer of an end product which contained DRAM may not know which manufacturer supplied the DRAM and that the only way to determine the manufacturer would be to open the device and remove the DRAM and look for the manufacturer’s mark. This could result in damage to or destruction of the product. He indicated that Hynix had only one direct customer in B.C., Seanix. It purchased on an ad hoc basis. The prices varied for each transaction. He described the market for its DRAM; the distribution chain for its products; the types of DRAM produced by Hynix; the various applications in which its DRAM is used; and the characteristics of its DRAM.

[47] John R. Cerrato, Vice-President of Global Sales for memory sales for Samsung. He deposed that during the proposed class period, Samsung’s DRAM sales in Canada, and in B.C. in particular, took place either from Samsung directly or through independent third party distributors. He deposed that no direct sales were made by Samsung to anyone located in B.C. He listed third party distributors of Samsung’s DRAM in North America. He stated that Samsung does not know if any of these third parties resold Samsung DRAM into B.C.; if there were, it does not know the location of the point of sale or the resale price. He described an example of the chain of how Samsung DRAM might find its way into a computer in B.C.

[48] Michael Bokan, Director of Sales for Micron. He has been employed with Micron for 7 years. He described the different varieties of DRAM and the manner in which they are sold, i.e. as components or in modules. He described Micron’s sales channels, customer categories and contracting approaches. He described a spot market into which Micron DRAM is sold. He described the various factors that affect pricing for the DRAM sold by Micron.

[49] None of the defendants’ witnesses were cross examined, except for Ms. Sanderson.

e) Dynamic Random Access Memory

[50] DRAM is a commonly used semiconductor memory product, which provides high-speed storage and retrieval of electronic information for a wide variety of computer, telecommunications and consumer electronics products. These products include: mainframe computers, personal computers, laptop computers, workstation computers, server computers, printers, hard disk drives, personal digital assistants, global positioning systems, modems, mobile phones, telecommunications hubs and routers, digital cameras, video recorders, televisions, digital set top boxes, game consoles and MP3 digital music players. Despite this wide variety of products, approximately 81 percent of DRAM is used in personal computers.

[51] There are also a wide variety of DRAM products that are manufactured and sold. They exist in different forms, sizes, speeds, storage capacities and qualities. DRAM is sold in three main forms:

(a) “bare die”, which are DRAM chips that are not packaged and that lack the connectors required to interface with other electronics;

(b) packaged “components”, which are single chips that have been finished with connectors so that they may interface with other electronics; and

(c) “modules”, which are small printed circuit boards onto which a number of DRAM components and other circuitry have been bonded and which may be connected to other electronics.

[52] The cost of DRAM as an input in various end-use products is typically a very small percentage of the price of the product. During the period from 2000-2002, the cost of DRAM was 0.2% of the average price of automotive products; 0.9% of the average price of industrial equipment; 0.3% of the average price of telecommunications products; and 0.8% of the average price of consumer applications. During the proposed Class Period, the input cost of DRAM varied from 1.1% to 8.6% of the average sale price of a major brand desktop personal computer and from 1% to 3.5% of the average price of a notebook computer, such as the Toshiba laptop purchased by the plaintiff.

[53] The supply chains that deliver DRAM from the manufacturer to the ultimate purchaser of that DRAM or of the product containing it can be long and multifaceted, involving a complex series of relationships. Through these chains, DRAM is moved between, packaged, and/or modified by various independent companies before they take their final form and reach their final destination.

[54] Mr. De Dios described the supply chain as follows:

The supply chain from the DRAM manufacturer to the consumer of the electronic system using the DRAM product is complex and resembles a web of relationships among different independent companies with different functions, rather than an orderly, hierarchical structure. The supply chain shows the existence of segments in the market that have their own cost, value, pricing and competitive dynamics. DRAM manufacturers are not direct participants in most of these supply chain segments.

[55] Mr. De Dios identifies ten groups of market participants through which a DRAM unit may flow following its manufacture and prior to reaching the ultimate consumer:

(1) value added manufacturers, which employ additional back-end manufacturing and packaging technologies to add value to the DRAM for specific applications;

(2) memory-based logistics and fulfillment companies, which provide several services to reduce an original equipment manufacturer’s (OEM’s) inventory risk while maintaining a supply of upgrade memory to its sale channels;

(3) processor manufacturers, which bundle DRAM products with their processors to deliver a differentiated product;

(4) spot market brokers, which buy and sell DRAM to make a profit;

(5) integrated circuit (IC) distributors and resellers, which buy DRAM from manufacturers and resell it to smaller OEMs;

(6) OEMs, which produce branded electronic products that use DRAM;

(7) original design manufacturers (ODMs) and contract manufacturers (CMs), which design and manufacture systems that are ultimately sold under an OEM brand;

(8) electronic system value added resellers (VARs) and system integrators, which buy DRAM from several different sources and convert them for use for specific applications and markets;

(9) electronic system distributors, which distribute products that use DRAM to resellers and retailers; and

(10) electronic system retailers, which sell electronic products to consumers.

[56] The supply chains through which DRAM units travel can take many forms, involving different market participants and different numbers of transactions. These variations can exist both between DRAM units that are destined for distinctly different end products (e.g. DRAM for a PC, DRAM for a cellular phone) as well as between DRAM units that will ultimately be used in the application as each other.

[57] By way of example, two DRAM units that will both be used in a PC may take very different routes along the various supply chains before a computer, within which they are installed, reaches a consumer. For instance, en route to being incorporated into a memory module, a DRAM component may be sold either directly to a memory module manufacturer or to a spot market broker who will, in turn, sell the component to the module manufacturer. Once the module is installed in a PC at an OEM, the DRAM unit may make its way directly to a consumer or be passed through different combinations of DRAM market participants, including distributors and retailers.

[58] Similar patterns emerge in the supply chains for different DRAM uses.

[59] Charts of the supply chain for the following major DRAM applications are found in the affidavit of Mr. De Dios: personal computers, servers, PC graphics and video game consoles, low power DRAM, and network communications. They are attached as Appendices A, B, C, D, and E, respectively.

[60] During the Class Period the weighted average price of DRAM moved in a fashion as depicted in the following graph attached to the affidavit of Ms. Sanderson:

[61] The plaintiff’s economic evidence related to the identification of pass-through harm to Class Members was provided by Dr. Ross. The defendants presented responding evidence from Ms. Sanderson.

[62] Dr. Ross’ first affidavit addressed the following five questions:

(i) Is it possible to assess whether direct purchasers of DRAM paid an overcharge due to cartel conduct?

(ii) Is it possible to quantify the price overcharge arising from any cartel conduct?

(iii) Is it possible to determine whether any DRAM price overcharge was passed through (in whole in part) to downstream purchasers of DRAM (i.e. to purchasers of products incorporating DRAM)?

(iv) Is it possible to quantify how much of any overcharge was passed through to downstream purchasers of DRAM?

(v) What is my preliminary opinion regarding whether direct and indirect purchasers were damaged by the price overcharge arising from any cartel conduct?

[63] Dr. Ross summarized his conclusions as follows:

My response to questions (i) through (iv) is “yes”. It is possible to assess and quantify the overcharge paid by direct purchasers of DRAM and it is possible to assess and quantify the extent to which these overcharges were passed through to downstream purchasers of products using DRAM, particularly computers. This analysis would make use of standard economic methods, including estimation using econometric methods. I believe that sufficient information is available to carry out such estimation effectively.

With respect to question (v), it is my preliminary assessment that both direct and indirect purchasers of DRAM were likely damaged by DRAM price overcharges.

[64] In his second affidavit Dr. Ross responded to the criticisms that were set out in Ms. Sanderson’s first affidavit. Her itemization of flaws is set out later. As part of his response he characterized Ms. Sanderson’s comments as a test against perfection. He stated the obvious that “[a] perfect result is never possible.”

[65] Dr. Ross then “sketched out” a procedure for measuring harm which included “simplifying assumptions”. In this regard he deposed:

28. As the affidavits of Ms. Sanderson and Mr. De Dios makes clear, the DRAM product class includes a number of differentiated products that are used in a wide variety of applications. This fact does not have to change the way I would go about measuring the harm caused by price fixing, but it will make it more demanding and costly than if this was a simpler commodity-type product with few downstream applications. This said, the high level of detail in these two affidavits is itself evidence that the expertise exists to trace through all these channels and markets if that is what the court desires.

29. I will now sketch out a procedure for evaluating the fact, amount and distribution of harm suffered by class members. This procedure would take advantage of four reasonable simplifications or simplifying assumptions that make the task much more tractable and straightforward than it would otherwise be.

30. The first simplification would come by dealing with harm on a national (i.e. pan-Canadian) basis. I understand that these class actions are being undertaken on a national basis by cooperating plaintiffs’ counsel so this seems very reasonable. This allows us, at the beginning, to avoid having to distinguish between purchases in British Columbia and the rest of Canada and having to worry about products that may have been “exported” from BC to the rest of Canada.

31. The second simplification recognizes that, at some level in the distribution chain, it may well be most efficient to distribute damages on a cy-pres basis as has been done in a number of other price-fixing class actions of which I am aware. It is not for me to say whether or not this is the way the distributions should be made, as this will be for the Court to approve. However, the availability of this option does mean that, if precise estimation of the allocation or distribution of harm is too costly to solve economically at some step in the consumption channel, there is an alternative available to the Court.

32. The third simplification recognizes the integrated nature of the North American markets for many (possibly most) electronics products. Low barriers to trade, the relatively high value of these products and the fact that many are imported into North America from other continents means that over time I would not expect prices to be much different across the borders or arbitrage would operate to close the gaps.

33. The fourth — and likely the most important — simplifying assumption would be to limit the focus of the analysis to one product channel. In this case it would be natural to focus on the personal computer channel as it represents, by a wide margin, the majority of DRAM use. Counsel to the proposed class have instructed me to focus my analysis on the overpricing of DRAM for the personal computer channel. This simplifies the analysis enormously. To the extent that other DRAM product channels are economically similar to the personal computer channel, it may be possible to apply the results derived from the personal computer channel to some other product channels.

[66] Ms. Sanderson in her critique of Dr. Ross’ first affidavit summarized her opinion as follows:

…the approach proposed by Professor Ross to estimate aggregate damages does not provide: (i) a class-wide method to determine whether any harm was sustained by any Class Members; or (ii) a class-wide means of ascertaining the extent of any such harm that any Class Member might have suffered. Furthermore, there is no alternative analysis that might be employed on a class-wide basis to determine either the fact of harm to the Class Members or the extent of such harm. To determine whether harm was sustained by any Class Member and to estimate the extent of such harm requires individual inquiries. Ultimately, this must be done product by product, direct purchaser by direct purchaser, for each level of distribution in each distribution chain, from direct to indirect purchasers, and then among indirect purchasers. The aggregate damages calculation proposed by the plaintiff offers no way around these difficulties.

[67] Ms. Sanderson opined that Dr. Ross’ approach has several flaws. She specified them in the following way:

23. Moreover, even if it can be established that the defendants imposed and sustained an overcharge on their direct purchasers, Professor Ross does not offer a class- wide methodology for determining the existence or extent of any “pass-through” of any such overcharge on DRAM to indirect purchasers. Because the class consists almost entirely of indirect purchasers, the only way to establish the existence of harm to Class Members is by demonstrating that the alleged overcharge was passed through to them. Professor Ross’s proposed “aggregate damages” method, by which he attempts to determine harm to these purchasers, is not a class-wide means of achieving this. The methodology is flawed in several key respects:

(a) The approach requires a determination of “first” indirect purchasers in British Columbia, but there is no class-wide method for identifying which indirect purchasers are the “first” ones in British Columbia;

(b) There exists no class-wide means to determine if the “first” indirect purchaser in British Columbia bought DRAM or products containing DRAM made by the defendants;

(c) Even if the “first” indirect purchasers in British Columbia could be identified and it could be established that they bought DRAM or products containing DRAM manufactured by the defendants (which is impossible using a common class-wide approach), it is impossible from a practical perspective to estimate the harm sustained by these customers;

(d) Many different products containing DRAM were sold during the Class Period, including desktops and laptops, enterprise and entry-level servers, workstations, mainframe computers, graphics cards, medical electronics, consumer applications such as video game consoles, digital set top boxes, automotive applications, and wireline and wireless telecommunications equipment such as switches, routers, and mobile handsets. These products have complex and variable distribution chains rendering analysis of pass through on a class-wide basis impossible, and highly impractical even on an individualized basis;

(e) Because of the differences in pass-through for different products and distribution channels it would be incorrect to apply the rate of pass-through for the “computer channel” (which in itself is expected to have different pass-through for the various products in this segment) to other products;

(f) Even if the alleged conspiracy was found to have had some effect on some sales of DRAM manufactured by the defendants to some customers, as noted above it was not likely effective in raising the prices of DRAM products to supra-competitive levels at all times, the result of which requires examining different overcharges at different times and hence different pass-through amounts to indirect purchasers of DRAM at different times;

(g) DRAM for many end products (which can be highly differentiated) represents a very small component in the overall cost of products containing DRAM, making it highly unlikely that any initial overcharge on DRAM can be causally linked to changes in the price of these end products sold to the “first” indirect purchasers in British Columbia;

(h) Some portion of any overcharge passed through to purchasers of products containing DRAM in British Columbia may have been passed out of British Columbia in the form of exported products; and

(i) The proposed aggregate damages approach would require enormous amounts of information, much of which is not publicly available and resides with non-parties to this proceeding, most of whom are located outside of Canada.

[68] In regard to Dr. Ross’ second affidavit, Ms. Sanderson is no less critical. She comments that Dr. Ross has devised a “new approach” and that he:

concedes the difficulty and impracticality of the task as the Class is defined in these proceedings. The simplifications contained in the Ross Reply really amount to attempting to estimate the existence and amount of harm for only two segments of DRAM purchasers in Canada (as opposed to British Columbia): (i) consumers who purchased DRAM contained in PCs purchased direct from a US-based PC manufacturer; and (ii) retailers that purchased DRAM contained in PCs purchased direct from a US-based manufacturer. To make these two inquiries provides no evidence on the fact or magnitude of harm to any other purchaser of any product (whether or not a PC) containing DRAM or even of DRAM itself.

Even these two inquires (which are for Canadian as opposed to British Columbia purchasers) will require individualized inquiries for which considerable information will be required (if they are to be anything other than simple guesses), much of which would need to be sought from non-parties outside Canada.

Assuming that price fixing took place in the manner that has been alleged is not equivalent to assuming that the Class Members have been harmed. As Professor Ross admits in his original affidavit, economic theory teaches that: “[t]he fact that collusion has occurred does not necessarily imply that the collusion has been successful in significantly raising prices above what they would otherwise be.” It is entirely plausible that the actual harm to the Class Member is zero. For example, the information that I have collected on PC advertised prices suggests it is highly unlikely that final product prices for PCs sold in British Columbia during the Class Period will be found to be higher as a result of any alleged DRAM overcharge. This, together with the evidence presented in my prior affidavit, suggest Class Members may not have been harmed at all, or alternatively that only a very small number of the Class Members would be found to have suffered any damage, even if it can in fact be established that DRAM prices were raised by the alleged conspiracy.

[69] She concluded that neither Dr. Ross’ new approach nor his amendments to his original approach provide a class-wide method to determine the existence or extent of harm to the Class as defined.

[70] Ms. Sanderson also rejected Dr. Ross’ characterization of her critique as a quest for perfection. She says it is rather a reflection of her view that his proposed methodologies are not class-wide means of determining whether any harm alleged to have been caused was passed through to Class Members.

[71] The goals of class proceedings legislation are judicial economy, access to justice, and behaviour modification, as explained by Chief Justice McLachlin in Hollick v. Toronto (City), 2001 SCC 68 at para. 15:

First, by aggregating similar individual actions, class actions serve judicial economy by avoiding unnecessary duplication in fact-finding and legal analysis. Second, by distributing fixed litigation costs amongst a large number of class members, class actions improve access to justice by making economical the prosecution of claims that any one class member would find too costly to prosecute on his or her own. Third, class actions serve efficiency and justice by ensuring that actual and potential wrongdoers modify their behaviour to take full account of the harm they are causing, or might cause, to the public.

[72] She also stated at para. 16:

[T]he certification stage is decidedly not meant to be a test of the merits of the action… Rather, the certification stage focuses on the form of the action. The question at the certification stage is not whether the claim is likely to succeed, but whether the suit is appropriately prosecuted as a class action.

[73] The Act is procedural in nature and does not create any new causes of action.

[74] Section 4 of the Class Proceedings Act requires that a plaintiff show that the proposed action meets a particular threshold before it will be certified to proceed as a class action.

[75] The threshold is composed of five criteria: the disclosure of a cause of action, the presence of an identifiable class, the presence of common issues, that a class proceeding is shown to be the preferable procedure, and that there is a suitable representative plaintiff.

[76] Specifically, s. 4 of the Act states:

4 (1) The court must certify a proceeding as a class proceeding on an application under section 2 or 3 if all of the following requirements are met:

(a) the pleadings disclose a cause of action;

(b) there is an identifiable class of 2 or more persons;

(c) the claims of the class members raise common issues, whether or not those common issues predominate over issues affecting only individual members;

(d) a class proceeding would be the preferable procedure for the fair and efficient resolution of the common issues;

(e) there is a representative plaintiff who

(i) would fairly and adequately represent the interests of the class,

(ii) has produced a plan for the proceeding that sets out a workable method of advancing the proceeding on behalf of the class and of notifying class members of the proceeding, and

(iii) does not have, on the common issues, an interest that is in conflict with the interests of other class members.

(2) In determining whether a class proceeding would be the preferable procedure for the fair and efficient resolution of the common issues, the court must consider all relevant matters including the following:

(a) whether questions of fact or law common to the members of the class predominate over any questions affecting only individual members;

(b) whether a significant number of the members of the class have a valid interest in individually controlling the prosecution of separate actions;

(c) whether the class proceeding would involve claims that are or have been the subject of any other proceedings;

(d) whether other means of resolving the claims are less practical or less efficient;

(e) whether the administration of the class proceeding would create greater difficulties than those likely to be experienced if relief were sought by other means.

[77] The plaintiff must establish an evidentiary basis – some basis in fact – with respect to each of the criteria, except for the first: Hollick; Caputo v. Imperial Tobacco Ltd. (2004), 236 D.L.R. (4th) 348 (Ont. S.C.J.); and Ernewein v. General Motors of Canada Ltd., 2005 BCCA 540, leave to appeal to S.C.C. refused, [2005] S.C.C.A. No. 545.

[78] The plaintiff sets the context of the case in stark and strong terms:

The defendants are admitted criminals who engaged in an international price fixing conspiracy that affected billions of dollars of commerce worldwide. With the exception of the Micron defendants, each of the defendants and/or their agents have pled guilty to antitrust conspiracy charges in the U.S., and agreed to pay hefty criminal fines.

[79] The plaintiff characterizes the conduct of the defendants as participants in a “hard core cartel” which is “the most egregious violation of competition law”: OECD, Recommendation of the Council concerning Effective Action Against Hard Core Cartels, Doc. No. C(98) 35/Final (Paris, 1998).

[80] The plaintiff argues that all of the statutorily required criteria are met and that this matter should be certified under the Act. It submits that at this stage of the proceeding the focus should be on the form of the action and not the merit of the claim, and that this is not the time to enter into an assessment of the positions of the parties’ respective experts or the likelihood that the plaintiff would be successful in any of the particular causes of action pleaded. Such inquiries are better left to the “laboratory of the trial court” where the parties can benefit from pre-trial discovery and a full evidentiary record.

[81] The defendants respond that the Courts have taken a hard look at class action certification applications regarding anti-competitive allegations and have concluded that the supporting evidence has not met the legal test for certification when the proposed class includes indirect purchasers. They emphasize that no such application has succeeded in Canada when contested. The key cases cited by the defendant in this regard are: Chadha v. Bayer Inc., (2001), 54 O.R. (3d) 520 (Ont. Div. Ct.), aff’d (2003), 63 O.R. (3d) 22 (C.A.), leave to appeal to S.C.C refused (2003), 65 O.R. (3d) xvii; Price v. Panasonic Canada Inc. (2002), 22 C.P.C. (5th) 379 (Ont. S.C.J.); Harmegnies c. Toyota, 2007 QCCS 539, aff’d 2008 QCCA 380.

[82] Chada dealt with a price fixing conspiracy action against manufacturers and distributors of iron oxide pigment. This pigment is used in making bricks, paving stones and other building materials. The class was described as the ultimate end-users of the products. Price dealt with a price maintenance action relating to the resale of various audio-visual products against Panasonic. The action was brought on behalf of an estimated 200 million end purchasers. Harmegnies dealt with a price fixing conspiracy against Toyota and 38 car dealers in the Montreal area. The action was brought on behalf of 37,000 purchasers or lessees of Toyota vehicles.

[83] The defendants specifically submit that the plaintiff’s evidence is as deficient as found in the above cases and does not meet the test for certification.

[84] They note that as a matter of policy in the United States, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that only direct purchasers, and not indirect purchasers, can recover damages in price-fixing cases because of the complexities and uncertainties of such proceedings and the resultant reduction in effectiveness of such suits, increase in cost of recovery, and reduction of benefits: Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977); see also Hanover Shoe v. United Shoe Machine Corp. 392 U.S. 481 (1968). However, the plaintiff notes that since Illinois Brick, many states have enacted legislation to permit indirect purchaser to bring class actions which have subsequently been successful in being certified.

[85] I note that cases in the American jurisprudence go both ways. The cases the plaintiff refers to include: Bunkers Glass Co. v. Pilkington PLC, 206 Ariz. 9, 75 P.3d 99 (S.C. 2003); Comes v. Microsoft Corp., 646 N.W.2d 440 (Iowa S.C. 2002); Cox v. Microsoft Corp., 8 A.D.3d. 39; 778 N.Y.S.2d. 147 (N.Y. App. 2004); In re Cardizem CD Antitrust Litigation, 200 F.R.D. 326 (2002); Hirsch v. Bank of America N.A., 107 Cal. App. 4th 708 (2003); Freeman Indus. LLC v. Eastman Chem. Co., 172 S.W.3d 512 (Tenn. 2005).

[86] The cases the defendants refer to include: Re: Methionine Antitrust Litigation, 204 F.R.D. 161 (N.D. Cal. 2001); A&M Supply Co. v. Microsoft Corp., 654 N.W.2d 572 (Mich. 2002); In re Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) Antitrust Litigation, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 44354 (N.D. Cal. 2007); In re Dynamic Random Access (DRAM) Antitrust Litigation (29 January 2008), file number M02-1486PJH (N.D. Cal.); Global Minerals and Metals Corp. v. Superior Court, 113 Cal. App. 4th 836 (2003), review denied, 2004 Cal. LEXIS 1781 (Cal. Sup. Ct.)

[87] The Supreme Court of Canada has not imposed an indirect purchaser limitation in Canada, however, the rationale found in Illinois Brick and Hanover Shoe runs through the three Canadian authorities that I have cited above.

[88] In Chadha, the Ontario Court of Appeal specifically referenced and acknowledged the observations in Illinois Brick of the complexity of finding price fixing effects on indirect purchasers. At para. 44 the court stated:

The complexity of the “pass-through” problem was recognized by the Divisional Court. The court referred with approval to the following passage from pp. 742-43 of Illinois Brick Co.:

in the real economic world rather than an economist’s hypothetical model,” the latter’s drastic simplifications generally must be abandoned. Overcharged direct purchasers often sell in imperfectly competitive markets. They often compete with other sellers that have not been subject to the overcharge; and their pricing policies often cannot be explained solely by the convenient assumption of profit maximization. As we concluded in Hanover Shoe, 392 U.S., at 492, attention to “sound laws of economics” can only heighten the awareness of the difficulties and uncertainties involved in determining how the relevant market variables would have behaved had there been no overcharge.

[89] The defendants argue that a detailed analysis shows that the proposed action is unsuitable for certification. The defendants claim that the plaintiff fails each of the five criteria laid out in the Act. They claim that given the nature of this case, certification would (using the words of Esson C.J.S.C. from Tiemstra v. ICBC (1996), 22 B.C.L.R. (3d) 49 at para. 20, aff’d (1997), 38 B.C.L.R. (3d) 377 (C.A.)) turn the case into a “monster of complexity and cost”, and that the process “will break down into substantial little trials.” The defendants submit that it follows that this action is unsuitable for a class proceeding. In this regard, the defendants point to the following aspects of this case:

1. the products vary in type and application;

2. the products in question are used merely as small inputs in another series of products;

3. the products are augmented or transformed after they are sold by the manufacturer;

4. the products travel through various complex supply chains;

5. the products are resold by several (and variable) levels of intermediaries in the supply chains;

6. the cost of DRAM is a small fraction of the cost of most of the many end products in which it is found;

7. the amount of any overcharge will be a small fraction of that small fraction;

8. whether the small fraction of the small fraction was passed on to the next purchaser, and the next and the next, until the product arrived in British Columbia will have to be ascertained; and

9. the evidence required to demonstrate that there was an overcharge and that it was actually included in the purchase price of the end products is highly complex and unavailable as a practical matter.

[90] The defendants argue that the immense size and scope of the proposed class, combined with the necessity of individual inquiries to establish harm, and the impossible complexity of identifying the consequent pass through analysis, is fatal to the plaintiff’s certification motion.

[91] The discussion and findings for each of the five criteria follow.

a) Disclosure of a Cause of Action

[92] The plaintiff submits that they have clearly disclosed and pleaded all requisite elements of: contraventions of Part VI of the Competition Act, tortious conspiracy, tortious interference with economic interests, unjust enrichment, waiver of tort, and constructive trust.

[93] The plaintiff acknowledges that there is uncertainty as to whether waiver of tort is an independent cause of action, whether all of the elements of unjust enrichment are required to recover under waiver of tort, and whether damages are essential for a claim in waiver of tort.

[94] However, it submits that recent cases in British Columbia and Ontario have found, at least at the pleadings stage, that waiver of tort can be framed as an independent cause of action, that all elements of unjust enrichment need not be pled to state a claim for waiver of tort, and that damages are not essential to a claim for waiver of tort. For these propositions, they cite Serhan (Estate Trustee) v. Johnson & Johnson, (2006), 85 O.R. (3d) 665 (Div. Ct.), aff’g 72 O.R. (3d) 296 (S.C.J.); Pro-Sys v. Microsoft Corp. 2006 BCSC 1047, Heward v. Eli Lilly Co., (2007), 47 C.C.L.T. (3d) 114 (S.C.J.), leave to appeal allowed in part (2007), 51 C.C.L.T. (3d) 167 (S.C.J.), and Lewis v. Cantertrot Investments Ltd., [2006] O.J. No. 1061, 2006 CarswellOnt 2737 (S.C.J.).

[95] Under waiver of tort, a plaintiff may waive its claim for tort damages and instead require the defendant to disgorge any gains flowing from its wrongful conduct.

[96] There is considerable discussion and debate in the legal literature and jurisprudence in Canada as to whether waiver of tort is an independent cause of action or simply a remedy. Under the latter, if damage is an element of the tort, the plaintiff will be required to prove damage as part of the tort prior to being able to elect to seek the gain obtained by the wrongful conduct of the defendant. Under the former, the requirement to prove damage as an element of a tort is obviated and the plaintiff is entitled to seek the gain obtained by the defendant upon proving the other elements of the cause of action.

[97] In Goff and Jones, Law of Restitution, 7th ed. (London: Sweet & Maxwell, 2007) at 36-0001, the learned authors state their view that:

“Waiver of tort” is a misnomer. A party only waives a tort in the sense he elects to sue in restitution to recover the defendant’s unjust benefit rather than to sue in tort to recover damages; he has a choice of alternative remedies. But the tort is not extinguished. Indeed, it is said the sine qua non of both remedies is that he should establish that a tort has been committed.

[98] In Reid v. Ford Motor Co., 2006 BCSC 712, the plaintiff in a negligence action sought the profits and savings of Ford from its avoidance of recalling certain vehicles. Gerow J. denied an application to add a claim of waiver of tort and stated as follows at paras. 27-28:

This action does not fall into the types of cases where waiver of tort has been applied and there is no principled basis on which to apply it in this case...

The underpinning of waiver of tort is that there has been some unjust enrichment to the defendant. Unjust enrichment is comprised of three elements:

1. an enrichment;

2. a corresponding deprivation; and

3. no juristic reason for the enrichment….

[99] Her comments at para. 33 are relevant to this case as it observes the requirement of directness of a benefit to the defendant:

The plea for revenue from the sales of replacement TFI modules must fail because the purchase price would have been paid to repair shops or parts dealers where the Class Members purchased the part and not to Ford. Any benefit to Ford was indirect and only incidentally conferred on them. Unjust enrichment does not extend to permit such a recovery. Cases where unjust enrichment has been made out generally deal with benefits conferred directly and specifically on the defendant, such as goods or services purchased directly from the defendant or money paid to the defendant: Boulanger v. Johnson & Johnson Corp., [2003] O.J. No. 2218 (C.A.); Peel (Regional Municipality) v. Canada, [1992] 3 S.C.R. 762.

[100] In Pro-sys v. Microsoft Corp., a case where the plaintiff alleged that they paid artificially inflated prices for the pre-installed Microsoft operating system and software applications as a result of Microsoft’s anti-competitive actions in the software market, Tysoe J. (as he then was) in refusing to strike a pleading of waiver of tort in the matter before him observed that the judgment in Lewis had been issued after the hearing of Reid but before issuance of the decision. He noted at para. 84 that Cullity J. stated at para. 7 of Lewis that:

In my opinion, the law relating to waiver of tort and restitution for breach of contract is, at present, too undeveloped and uncertain to permit a decision – in the context solely of the pleadings – that the availability of either remedy will require the plaintiffs to establish that the three pronged test of unjust enrichment is satisfied…

[101] Tysoe J. at para. 85 then distinguished Reid on the basis that:

Gerow J. held there that the flaw in the claim for unjust enrichment was an absence of the required enrichment. It may well be concluded that a plaintiff seeking to rely on the doctrine of waiver of tort is not required to prove the absence of a juristic reason for the enrichment because the plaintiff will have been successful in proving that the defendant did commit a wrong that resulted in the enrichment. In my opinion, it is not plain and obvious that the Plaintiff will have to establish all elements of unjust enrichment (and, in particular, the absence of a juristic reason for the enrichment) before being entitled to rely on the doctrine of waiver of tort.

[102] Tysoe J. did however, strike the claim of constructive trust on the basis that the statement of claim as amended by his earlier ruling no longer pleaded either of the quasi-alternative grounds set out in Soulos v. Korkontzilas, [1997] 2 S.C.R. 217, being unjust enrichment and wrongful acts in the context of an equitable obligation. In regard to the latter, his view at para. 91 of McLachlin J.’s statement in Soulos regarding the limits to the availability of the remedy is informative:

The comments of McLachlin J. … must be read within the context of her reasons as a whole. She was not indicating that constructive trusts are available for all types of wrongful acts. Her comments at [paragraph] 34 indicate that one of the purposes of a constructive trust based on “good conscience” is to maintain the integrity of institutions dependent on trust-like relationships. This is made clear by the first two of the four conditions that McLachlin J. identified at [paragraph] 45 as prerequisites for a constructive trust based on wrongful conduct (as opposed to unjust enrichment):

1. The defendant must have been under an equitable obligation, that is, an obligation of the type that courts of equity have enforced, in relation to the activities giving rise to the assets in his hands;

2. The assets in the hands of the defendant must be shown to have resulted from deemed or actual agency activities of the defendant in breach of his equitable obligation to the plaintiff;

It is clear in the present case that the Defendants were not under any equitable obligation and that the monies representing the “overcharge” did not result from any type of agency activities of the Defendants.

[103] There are two notable cases from Ontario: Serhan and Heward.

[104] In Serhan, at first instance, Cullity J. certified the action. The action was based on allegations of negligence, negligent and fraudulent misrepresentation, breach of the Competition Act, and conspiracy relating to the defendants manufacture, sale and distribution of allegedly defective blood glucose meters and testing strips. Though waiver of tort was not pleaded, Cullity J. found that on the materials before him the plaintiffs could be entitled to a remedy under the doctrine of waiver of tort.

[105] On the appeal of the case, a majority of the Divisional Court upheld the decision of Cullity J. Writing for the majority Epstein J. (as she then was) provided a detailed review of the concept of waiver of tort and covered the cases and academic writing that represented the two views. She concluded that the matter had not been authoritatively settled and agreed with Cullity J. that the issues of whether waiver of tort is an independent cause or not should be resolved with the benefit of a “more fully developed record”: para. 69.

[106] Chapnik J., in her dissent, found that the facts of the case did not justify certification based on waiver of tort. She stated at para. 164 that the case “[did] not fall within the types of cases where waiver of tort has been applied, and it is plain and obvious that there is no principled basis on which to apply it in this case.” She concluded that it was plain and obvious that the action would fail. She found that the restitutionary remedies of constructive trust and disgorgement were certain to fail because of the “combined absence of the elements of unjust enrichment, any trust-like relationship, or any sort of calculable loss or ongoing deprivation suffered by the representative plaintiff or member of the putative class in relation to the defendants’ profits”: para. 200.

[107] Chapnik J. noted that the restitutionary remedy based on unjust enrichment was unavailable given the lack of deprivation and also noted the lack of any direct relationship between the parties as a basis similar to the finding in Boulanger and Reid. She also rejected the constructive trust claim based on wrongful conduct as opposed to unjust enrichment because the four conditions set out in Soulos had not been met.

[108] A further policy issue raised at para. 253 of the dissent was a concern that a certification based on waiver of tort would introduce strict liability for defective products and that the circumstances did not lend themselves to a proper testing of the concept.

[109] A further perspective on the topic can be seen in the comments of Lederman J. in the leave to appeal ruling in Heward. The case involved the sale of an antipsychotic drug, manufactured and sold by the defendant, which was alleged to increase the risk of diabetes and related side-effects which the defendant was said to have failed to disclose or warn users and physicians. He granted leave to appeal the certification on the following issues at para. 44:

1. Did the certification motion judge err in concluding that proof of the amount of the alleged wrongful gain subject to an accounting and disgorgement and/or a constructive trust is a common issue?

2. Did the certification motion judge err in concluding that a class proceeding, is the preferable procedure to resolve the plaintiff’s claim in waiver of tort?

[110] In making his determination, Lederman J. questioned whether proof of the amount to be disgorged or held in a constructive trust was a common issue. In this regard, he stated at paras. 26-28, 32:

26 …Serhan does not change the requirement that there be proof of a “wrongful gain” that will be subject to disgorgement or a constructive trust. Generally speaking, a gain is a ‘wrongful gain’ only if it is attained through “wrongful conduct”; i.e. the wrongful conduct must cause the gain. Consequently, for the amount subject to disgorgement and constructive trust to be a common issue in this class action, the pleadings and evidence must demonstrate a way to prove on a class-wide basis that the alleged wrongful conduct (i.e. ‘the failure to warn’) caused the gain (i.e. ‘proceeds from Zyprexa sales’).

27 At para. 101 of his reasons Cullity J. said,

The finding that a cause of action based on waiver of tort has been disclosed in the pleading is not in itself sufficient to qualify it as a common issue. In particular, the court must be satisfied that it is possible to determine on a class-wide basis whether a sufficient causal connection existed between the wrongful conduct and the amount for which the defendants could be ordered to account.

28 Cullity J. was correct in stating there must be a causal connection on a class-wide basis between the gain subject to disgorgement or constructive trust and the wrongful conduct.

…

32 In this case, and with great respect, it is not clear to me that the pleadings or the evidence support the assumption made by Cullity J. that Eli Lilly's gain was caused by its wrongful conduct. While the pleadings explicitly say the primary plaintiffs would not have taken the drug if they had been informed of its alleged side-effects (see Cullity J.'s reasons at para. 47), neither the pleadings nor the evidence support the inference that all members of the class would have done the same. This is perhaps not surprising, given that Zyprexa continues to be prescribed and used by persons, including class members, three years after Health Canada ordered Eli Lilly to issue warnings regarding the possible risk of developing diabetes when taking Zyprexa. There is also nothing in the pleadings or the evidence to support the inference that Zyprexa would not have been approved for sale if Health Canada was properly warned of its associated risks. And since Health Canada was in fact warned about the risks of Zyprexa use in late 2003 and has not ordered the drug off the market, it is difficult to infer that Health Canada would not have approved Zyprexa in the first place if it received these same warnings in the early 1990's.

(Emphasis of Lederman J.)

[111] To refuse to certify a class action on the basis of the first criteria, it must be “perfectly clear”, “absolutely beyond doubt” and “plain and obvious” that no reasonable cause of action is disclosed in the pleadings.

[112] The character of waiver of tort obviously remains unsettled. Accordingly, it would be premature to deny certification for this cause of action on the basis of the first criteria.

[113] As to the constructive trust claim, the reasoning in Pro-Sys v. Microsoft and that of Chapnik J. in Serhan is applicable here. No equitable obligation or agency type activity is pleaded capable of supporting the wrongful act route to a constructive trust. However, as a constructive trust is also claimed through the unjust enrichment route – the second route described in Soulos – the constructive trust claim is not to be struck in its entirely. I would order that any pleadings related solely to the wrongful act route to constructive trust be struck, but those related to the unjust enrichment route to constructive trust be permitted to remain.

[114] I conclude that with the exception just outlined, the pleadings meet the requirements of the first threshold criteria for certification.

[115] Having made this finding on the pleadings, the other threshold questions require an assessment of the evidence presented regarding whether the plaintiff has met each of the criteria. A particular difficulty in this regard is the establishment of liability on a class wide basis. This and other matters are addressed in the sections that follow.

[116] Identification serves three key purposes:

· It identifies those persons who have a potential claim for relief against the defendants;

· It defines the parameters of the lawsuit so as to identify those person who are bound by its result; and

· It describes who is entitled to notice pursuant to the Act, so that the class members may determine whether they wish to participate in the class proceeding, have their right determined in another fashion, or take no action.

[117] I would add that it also serves to inform the question of the preferable procedure: Lau v. Bayview Landmark Inc. (1999), 40 C.P.C. (4th) 301 (Ont. S.C.J.) at para. 26.

[118] The appropriate time to define the class and to exclude those without claims is at the time of certification: Western Canadian Shopping Centres v. Dutton, 2001 SCC 46 at para. 38.

[119] The definition should state objective criteria by which Class Members can be identified. Some rational relationship must be shown to exist between the class and common issues. It is not a requirement that all members of a class share the same interest in the determination of a common issue; however, the proposed class must be shown not to be “unnecessarily broad”. While identification is critical, this requirement is said to be not an onerous one; the plaintiff has the onus to establish that the class is defined “sufficiently narrowly”: see Hollick at paras. 20-21.

[120] As mentioned at the outset, the plaintiff in its written submission clarified the proposed class to be all residents of British Columbia who purchased DRAM and products containing DRAM directly, and indirect purchasers of the same, in, into, or from British Columbia. Further, the plaintiff has named other conspirators in its amended consolidated statement of claim which covers much of the balance of DRAM not manufactured by the defendants. Apparently, these other conspirators were named as defendants in the U. S. direct purchaser class action and several have settled their claims.

[121] It is fair to say that this class has the potential to be enormous given the vast number of products containing DRAM.

[122] The plaintiff submits that there are two legal principles that support the appropriateness of the proposed class:

· Not all class members must have a cause of action against the defendants; rather, that it is sufficient that all class members may have a cause of action against the defendants even if it is only a smaller segment of the class that actually suffered a harm; and

· Enunciating the precise definition of the class is a fluid process, which only need reach a conclusion when, pursuant to section 8 of the Act, it is included in the order of the court.

[123] The plaintiff submits that further differences or issues between class members can be addressed through the use of sub-classes or on an individual basis.

[124] The defendants submit that the class definition is unsuitable as it fails to take into account both the effect of the Settlement Agreements in the United States which release the defendants from liability to direct purchasers in the United States, and Dr. Ross’s evidence that most direct purchasers of DRAM were not part of the class.

[125] The defendants argue that the class, as defined by the plaintiff, is over-inclusive as it could have been narrowed without unnecessarily excluding individuals who ought to have been class members. Indeed, the defendants characterize the proposed class as “boundless”. Thus, the defendants argue that the proposed class needs to be redefined.

[126] They also argue that there is no evidence before the court capable of grounding a reasonable estimate of the size of the proposed class. The defendants’ evidence reveals that they have little evidence of who purchased their products in British Columbia. It is obvious from the evidence of the plaintiff that they have little evidence that can assist. Neither Mr. Leung nor Mr. Mogerman were able to provide any specific measure of the size of the proposed class.

[127] A further complication argued is that the proposed Class Members cannot in many cases objectively self identify themselves as being in the class. The consumer will not be able to tell if their product contains DRAM and, even if they can, the consumer will most likely not know whether the DRAM was manufactured by the defendants. The materials indicate that in most circumstances, the only method for the individual consumer to determine the manufacturer is by opening or disassembling the product and to inspect its circuitry and memory chips. However, by taking such steps, the consumer will be exposed to potential costs and risks, including product damage and voidance of product warranties.

[128] It is also notable that Dr. Ross’ evidence in his second affidavit proposed a pan-Canadian approach which is not consistent with the definition proposed by the plaintiff.

[129] There are problems with the class proposed by the plaintiff. The plaintiff’s modifications of the class definition, including during the course of the hearing, suggests there are difficulties with crystallizing the class given the complex issues in this case. There are incongruencies in the way they have presented this case. However, I recognize that the exercise in defining a class is a fluid one and that while it is important to get things right at the outset, I do not find that the issues raised by the defendants are sufficient barriers to bar certification on this ground, except that the inclusion of direct purchasers of DRAM (and their affiliates, agents, and shareholders etc.) who have settled in actions against the defendants in the United States are to be excluded from the definition.

[130] Commonality is the linch pin of a class proceeding. In Ernewein at para. 32 the court quoted from Harrington v. Dow Corning Corp., 2000 BCCA 605 at para. 24 to the effect that “‘common’ means that the resolution of the point in question must be applicable to all those who are to be bound by it” and thus, the ability to generalize, or “extrapolate” from one class member’s situation to another is crucial to the existence of a common issue.

[131] While the common issues do not have to be issues that are necessarily determinative of liability for every defendant, their resolution must move the litigation forward in a meaningful way. In that sense, the inquiry must not consider commonality in the abstract, but must consider the importance of the common issues relative to the claim as a whole. As well, common issues are not synonymous with common causes of action.

[132] It is also clear that it is not the quantity of commonalities but their quality that is the governing factor when it come to evaluating the commons issues criterion: 2038724 Ontario Ltd. and 20362350 Ontario Inc. v. Quizno’s Canada Restaurant Corporation [2008] O.J. No. 833 (S.C.J.) at para. 104.

[133] The plaintiff submits that certifying this action will avoid the duplication of fact-finding and/or legal analysis that would be substantial and essential elements of each Class Member’s claim. Specifically, the plaintiff claims that the dominant issue of liability and the corresponding questions as to the existence, scope and efficacy of the conspiracy to fix the prices of DRAM, are common issues that are suitable for class proceedings: Ritchie-Smith Feed Inc. v. Rhône-Poulenc Canada Inc., 2005 BCSC 583 which adopted the reasoning of Cumming J. in Vitapharm v. F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd. (2005), 74 O.R. (3d) 758 (S.C.J.).

[134] The common issues identified by the plaintiff are:

Breach of the Competition Act

(a) Did the defendants, or any of them, engage in conduct which is contrary to s. 45 of the Competition Act?

(b) What damages, if any, are payable by the defendants to the Class Members pursuant to s. 36 of the Competition Act?

(c) Should the defendants, or any of them, pay the full costs, or any, of the investigation into this matter pursuant to s. 36 of the Competition Act?

Conspiracy

(d) Did the defendants, or any of them, conspire to harm the Class Members?

(e) Did the defendants, or any of them, act in furtherance of the conspiracy?

(f) Was the predominant purpose of the conspiracy to harm the Class Members?

(g) Did the conspiracy involve unlawful acts?

(h) Did the defendants, or any of them, know that the conspiracy would likely cause injury to the Class Members?

(i) Did the Class Members suffer economic loss?

(j) What damages, if any, are payable by the defendants, or any of them, to the Class Members?

(k) Can the amount of damages be determined on an aggregate basis and if so, in what amount?

Tortious Interference with Economic Interests

(l) Did the defendants, or any of them, intend to injure the Class Members?

(m) Did the defendants, or any of them, interfere with the economic interests of the Class Members by unlawful or illegal means?

(n) Did the Class Members suffer economic loss as a result of the defendants’ interference?

(o) What damages, if any, are payable by the defendants, or any of them, to the Class Members?

(p) Can the amount of damages be determined on an aggregate basis and if so, in what amount?

Unjust Enrichment, Waiver of Tort and Constructive Trust

(q) Have the defendants, or any of them, been unjustly enriched by the receipt of overcharges on the sale of DRAM?

(r) Have the Class Members suffered a corresponding deprivation in the amount of the overcharges on the sale of DRAM?

(s) Is there a juridical reason why the defendants, or any of them, should be entitled to retain the overcharges on the sale of DRAM?

(t) What restitution, if any, is payable by the defendants, or any of them, to the Class Members based on unjust enrichment?

(u) Should the defendants, or any of them, be constituted as constructive trustees in favour of the Class Members for all of the overcharges from the sale of DRAM?

(v) What is the quantum of the overcharges, if any, that the defendants, or any of them, hold in trust for the Class Members?

(w) What restitution, if any, is payable by the defendants to the Class Members based on the doctrine of waiver of tort?

(x) Are the defendants, or any of them, liable to account to the Class Members for the wrongful profits that they obtained on the sale of DRAM to the Class Members based on the doctrine of waiver of tort?

(y) Can the amount of restitution be determined on an aggregate basis and if so, in what amount?

Punitive Damages

(z) Are the defendants, or any of them, liable to pay punitive or exemplary damages having regard to the nature of their conduct and if so, what amount and to whom?

Interest

(aa) What is the liability, if any, of the defendants, or any of them, for court order interest?

Distribution of Damages and/or Trust Funds

(bb) What is the appropriate distribution of damages and/or trust funds and interest to the Class Members and who should pay for the cost of that distribution?

[135] In particular, the plaintiff submits that the dominant issue of liability is common:

Did the defendants’ conspire to fix the price of DRAM?

What was the scope of the conspiracy?

What was the effect of that conspiracy?

[136] The plaintiff submits that once these dominant common issues are resolved by the court, there are “class-wide, and therefore common, ways of determining causation and damages.”

[137] The issues the plaintiff says can be addressed and answered on a class-wide basis are:

(a) Was the conspiracy effective in raising prices to direct purchasers, including some of the Class Members?

(b) Did indirect purchasers, including the remaining Class Members, pay more because of the conspiracy?

(c) Did the defendants profit because of the conspiracy?

(d) Are the class members entitled to punitive damages and, if so, in what amount?

[138] The parties effectively agree that the issues relating to the existence of the conspiracy to fix prices for DRAM are common among the proposed Class Members. The argument of the defendants is that there is no methodology for establishing harm on a class-wide basis. The defendants say that no credible methodology has been proposed to establish that there was a pass through of a price fixing effect to the vast majority of subsequent indirect purchasers caught by the proposed class definition, let alone a methodology capable of estimating the amount of such an effect even in approximate terms. The defendants say that this failure is fatal to the plaintiff’s application for certification.